Why do writers kill themselves? Such a question has remained a touchy subject that many people have eventually equated suicide to the consummation of the artistic life. When David Foster Wallace hanged himself on 2008, it was mainly attributed to his personal issues. Ernest Hemingway ended his life through a shotgun to a head also because of a bunch of problems. One of my favorite writers, Yukio Mishima, committed seppuku as the final act for a life “turned into a line of poetry tinged with blood.” I just think he just don’t want to get too old.

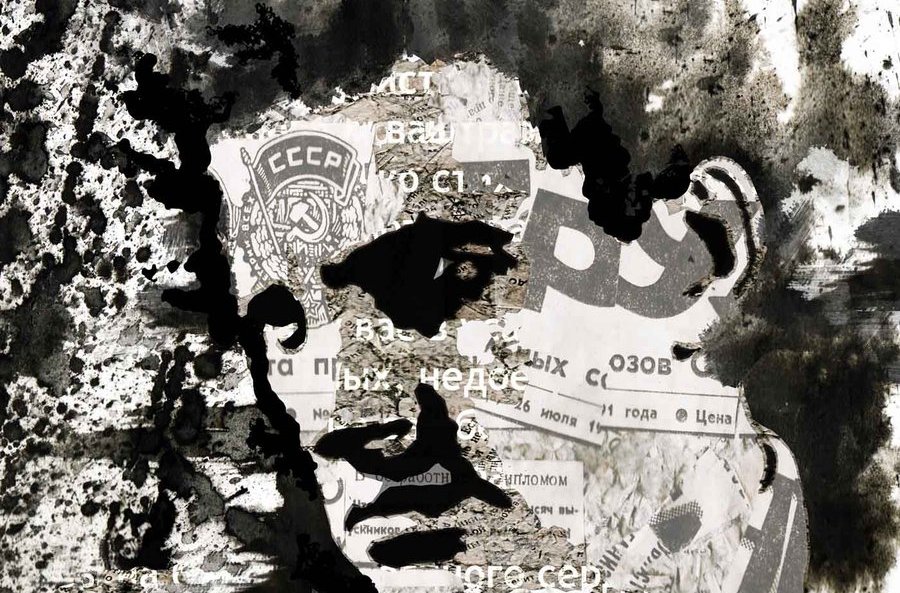

That is why I consider it odd that Soviet Russia’s premiere poet-visionary, Vladimir Mayakovsky (also one of my beloved poets) committed suicide due to depression on April 14 1930. Part of his suicide letter suggests that it was because of disappointed love (the letters comes with a poem, read it here):

And so they say,

“the incident dissolved”

the love boat smashed up

on the dreary routine.

I’m through with life

and [we] should absolve

from mutual hurts, affliction and spleen.

This is odd, because Mayakovsky poetry it seems, always gravitates towards the harmonious integration of the individual (sentiments, ambitions) to the universal mission of social emancipation. His constant rebuking of sentimentalism, especially among poets and artists, always leads to the exhortation of pursuit of larger aims, which in Mayakovsky’s case is the advancement of socialism . For instance, in his tribute to Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, he stressed the power of collective action through the Party:

Words—

Even the finest—

Turn into litter,

Today

I want to infuse

New glitter

Into the most glorious of words:

PARTY.

Individual—

What can he mean in life?

His voice

sounds fainter

than a needle dropping.

Who hears him?

Only, perhaps his wife,

And then if she’s near

And not out shopping.A Party’s

A raging,

Single-voiced storm

Compressed

Out of voices

Weak and thin.

Mayakovsky’s valorization of the Party, socialism, and his often piercing admonition of capitalism expressed through utter disgust and often taunting humor, marks his poetry as an attempt to push experiential boundaries. By making sense of the new social order that the Soviet Revolution was pushing, Mayakovsky’s poetry molded the individual as the smallest indispensable detail in its actualization. Selfish sentiment is an excess of liberal society.

Or is it? While reading Mayakovsky, I sensed his futurist enthusiasm seems to be come from old romantic notions. In expressing calls like ‘rebuke the individual!’, ‘on towards Communism!’, etc., he always seems to come from his own ancient regime love of these very things. For instance, in “Cloud in Pants,” Mayakovsky told a story of a hopeless romantic turned ‘true man.’ Regarding his romantic past:

Or is it? While reading Mayakovsky, I sensed his futurist enthusiasm seems to be come from old romantic notions. In expressing calls like ‘rebuke the individual!’, ‘on towards Communism!’, etc., he always seems to come from his own ancient regime love of these very things. For instance, in “Cloud in Pants,” Mayakovsky told a story of a hopeless romantic turned ‘true man.’ Regarding his romantic past:

If you want—

I can be all crazy flesh

The antipode of polite romance.

Or

Sweet and delicate as you wish;

Not a man but a cloud in pants

Going through the poem, we sense that what Mayakovsky is trying to relay is that the transformation of the individual, from selfishness to selflessness, is a struggle that never ends; that is, one never truly transforms from a ‘cloud in pants’ into a ‘man’ absolutely. There is an unending tension between the individual and the world, especially in a radically changing world, such as in Soviet Russia. While admonishing the corrupt world, he seems to me, rather imperfect after all. Mayakovsky remains a romantic , only with a conscience and a longing for something absolutely new.

Leon Trotsky takes this same subject quite differently. He proposed that Mayakovsky’s suicide is the result of the irreconcilable discord between his bourgeois self and the ideal his conscience is pressing on him. Trotsky explains:

To view the question in its broadest dimensions, Mayakovsky was not only the “singer,” but also the victim, of the epoch of transformation, which while creating elements of the new culture with unparalleled force, still did so much more slowly and contradictorily than necessary for the harmonious development of an individual poet or a generation of poets devoted to the revolution. The absence of inner harmony flowed from this very source and expressed itself in the poet’s style, in the lack of sufficient verbal discipline and measured imagery. There is a hot lava of pathos side by side with an inappropriate palsy-walsy attitude toward the epoch and the class, or an outright tasteless joking which the poet seems to erect as a barrier against being hurt by the external world.

Further in the article, Trotsky brought up the political context of Mayakovsky’s death. He explained that Party bureaucracy put pressures on Mayakovsky and his poetry, especially since he has constantly refused to become a member of the state-sponsored VAPP or All-Union Association of Proletarian Writers. However, two to three months before his suicide, he finally joined the union despite his previous disapproval of the group’s artistic inclinations which at that time was slowly waxing from the Russian avant garde towards Stalinist social realism. Because of this, Trotsky reasons, Mayakovsky, “defeated by the logic of the situation, committed violence against himself.”

But was Mayakovsky’s suicide justified, whatever his reasons may be? Is it fair for Trotsky to frame suicide simply as the result of an incapability to resolve these contradictions?

Read Mayakovsky’s poems here.